Former university lecturer Cherry Coombe had pneumonia in April 2022 which turned to sepsis. She was put in an induced coma which led her to experience delusions that the very people who were trying to save her were trying to hurt her.

She is sharing her story with the UK Sepsis Trust so that others may be more comfortable talking about their experiences in hospital…

Cherry was 65 when she had pneumonia that initially went undiagnosed due to admin errors at her local GP surgery. She was at home one day when a friend that had come to collect a prescription for her, soon realised that she needed to contact 111 because Cherry was behaving very peculiarly.

What happened next is a bit of a blur for Cherry, but her daughter who lives in Cambodia had called her to find her mum talking nonsense. Cherry said: “She then rang my brother and said, I think your sister’s drank a bottle of vodka. You’ve got to get round there. Now. She’s had a stroke or something. Usually my brother doesn’t respond very well to emergencies because he thinks I’m a bit of a drama queen. But fortunately, my daughter and my friend had rung him up and his wife said, ‘I think we’d better go and get her’.”

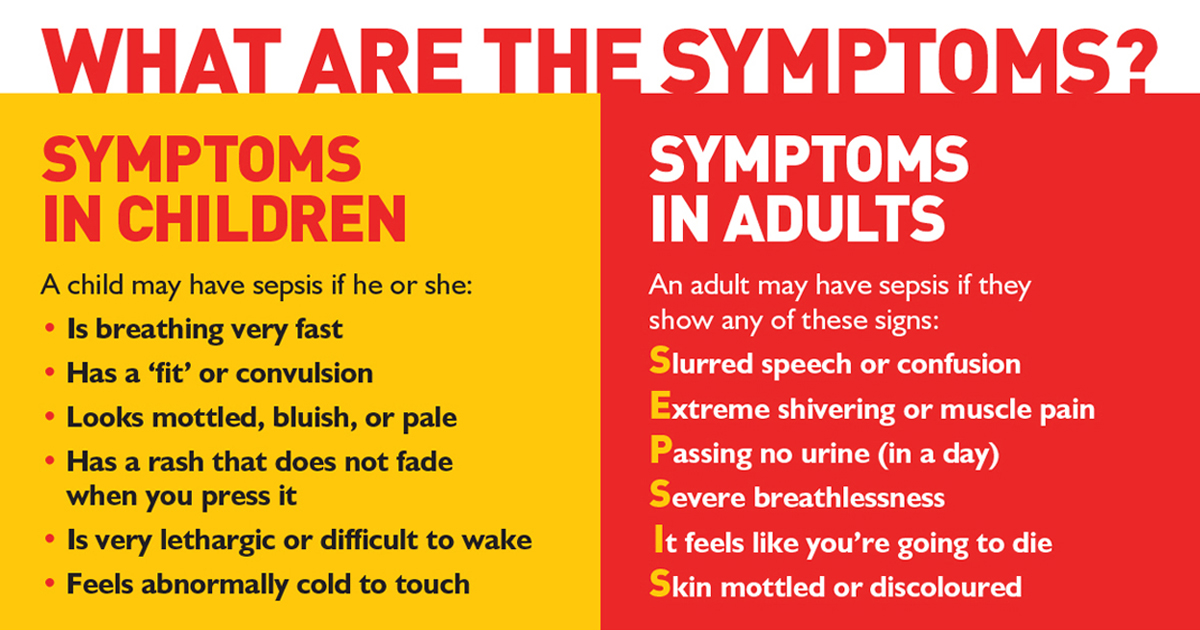

Her sister-in-law has since told Cherry that she was very cold to touch – a sign of sepsis – and despite putting up a fight, made it to hospital in Banbury. The hospital was selected over Milton Keynes primarily because it was easier for her brother and sister-in-law to visit, but it turned out to be a blessing. Cherry said: “I was raving mad, completely mad, and I didn’t want to go in there because I thought I’d never get out. But just by some fluke, someone there recognized that I was so cold, I was so delirious, I hadn’t been weeing, and that the pneumonia had progressed to sepsis.”

Cherry was transferred from the smaller hospital to one in Oxford and put in an induced coma. Her son flew back from Indonesia to be with her. Cherry said: “It was horrendous. I thought I’d been taken hostage. My imagination was going insane. To my mind, I’d been captured by very dangerous, evil people who’d got me in an airport hangar and tied me up, they gagged me, they were tormenting me. And then when my son came, I felt he wasn’t safe either. I couldn’t speak, they wouldn’t give me water.”

But despite concerns for her son’s safety, Cherry believes her son was her saving grace. She said:

“My son arrived just at the right time because I don’t really believe all that science works without love.

“So, there I was thinking, ‘I’ll just give up now. I cannot sustain this any longer.’ And then I heard my son’s voice, and I could feel he was holding my hands and he was saying, ‘It’s me, mum, it’s really me. I really am here. Can you open your eyes?’ and it was so powerful. I couldn’t have got through this without so much love.”

After waking up from the coma, she was warned that she might need dialysis, could have some brain damage and may not be able to walk. Still struggling with her speech, Cherry was determined not to stay in the hospital which she viewed as a prison. She said: “Some people told me I was incredibly naughty. I ripped out all these lovely, horrible things they had got in my arm, blood everywhere. I was trying to chew through all the things in my mouth that they were giving me air or food through. I thought it was petrol and drugs to make me go mad. I was trying to desperately get out of there. I think it’s normal. I keep having flashbacks to that. It’s really horrendous not to have any power.”

Cherry hopes by sharing her own story, others will be tempted to share theirs and realise that it is common to experience psychological issues while in critical care and recovery. She said:

“I’d really like to help people examine that coma experience because it’s very peculiar when people are trying to do something to bring you back to life and you have the experience of them trying to finish you off completely.”

After the coma, Cherry had a series of dreams such as being in a meeting at work with people going ‘Don’t take any notice of her’ and walking off or being in a shop and being unable to get the woman to let her buy cheese. A friend found the UK Sepsis Trust via a Google Search, which helped Cherry begin to navigate her experience of critical care and the confusing lack of agency that followed. She said: “Every dream I had was about being completely disempowered, having no choice, no agency, no ability to make an impression on people. It took a lot of working with Oliver at the UK Sepsis Trust – who I’m now almost totally dependent on – to help me understand that’s normal. Without him I wouldn’t be alright, I’d be much more lost than I am.”

After emerging from the coma, Cherry embarked on physiotherapy, but initially found it difficult to accept praise for things like moving up in the bed or sitting on a chair as anything other than patronising. Now, a year later, she can walk five miles, but she struggles to do tasks involving reaching into the top cupboard or carrying heavy objects – because she only did half her physio exercises. She advises others against this: “Listen to the physiotherapists, even though they come across like nasty schoolteachers.”

With the benefit of hindsight, Cherry said: “I should have carried on physically recovering, pushing myself and allowed myself to be more like a helpless baby emotionally. I was too hard on my emotional self; I wasn’t saying, ‘Oh great, well done, you’ve done three steps’ to myself because I feel that the physiotherapists were patronizing me in hospital. I can see the value of that now. ‘Well done, you’ve had a wash’. I would be dismissive, ‘Well, of course I’ve had a wash. You don’t want me stinking do you?’ I’ve been hard on myself, so I would tell anyone do as much as you can physically can to look after yourself and nurture yourself, but included to that be really, really kind to yourself – you’ve been through living hell.”

Another bit of advice for others, is about being persistent when you need to be. Cherry said: “I think it’s important that we all remember that we help our GPs when we keep in touch with them and it’s not easy. And I think after COVID, we’ve got to really learn that it’s okay to go to the doctors when you’re ill.”

One good thing that has emerged from Cherry’s time in critical care is her positive outlook. She said: “Nearly all of me is intact except for a bit of my lung, and also the negative part of me seems to have gone out the window. I can’t help being really quite pleased just to be alive, even if it’s raining, even if I’ve eaten something I don’t really like that someone else has cooked, or even if I put on a bit of weight. I just can’t help being quite glad to just simply wake up every day.”

She added: “My son flew in and my daughter flew in when she could. And there were so many people that were invested in making me better. They loved me and I was so surprised that so many people were willing to help me. It’s almost as if a part of me would be ashamed of not being positive about it. Part of me feels I owe it to everybody else to make the best of what’s left of life.”

Now retired, Cherry is writing about her experiences in hospital as a way of processing what happened to her. She encourages others to find an outlet for their stories too.